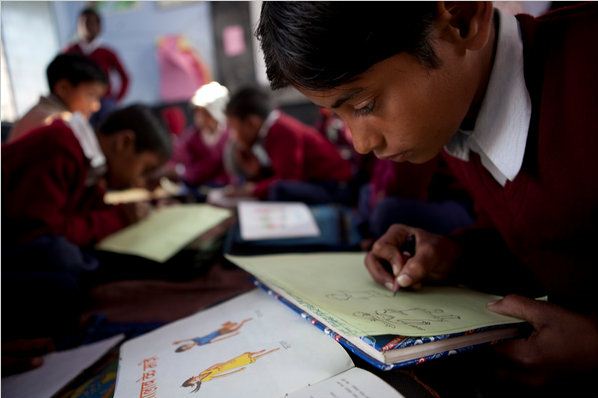

That might seem commonplace in American or European schools. But such activities are revolutionary in India, where public school students have long been drilled on memorizing facts and regurgitating them in stressful year-end exams that many children fail.

Nagla and 1,500 other schools in this Indian state, Uttarakhand, are part of a five-year-old project to improve Indian primary education that is being paid for by one of the country’s richest men, Azim H. Premji, chairman of the information technology giant Wipro. Education experts at his Azim Premji Foundation are helping to train new teachers and guide current teachers in overhauling the way students are taught and tested at government schools.

For Mr. Premji, 65, there can be no higher priority if India is to fulfill its potential as an emerging economic giant. Because the Indian population is so youthful — nearly 500 million people, or 45 percent of the country’s total, are 19 or younger — improving the education system is one of the country’s most pressing challenges.

“The bright students rise to the top, which they do anywhere in any system,” Mr. Premji said over lunch at Wipro’s headquarters in Bangalore, 1,300 miles south of Uttarakhand. “The people who are underprivileged are not articulate, less self-confident, they slip further. They slip much further. You compound a problem of people who are handicapped socially.”

Outside of India, many may consider the country a wellspring of highly educated professionals, thanks to the many doctors and engineers who have moved to the West. And the legions of bright, English-speaking call-center employees may seem to represent, to many Western consumers, the cheerful voice of modern India.

But within India, there is widespread recognition that the country has not invested enough in education, especially at the primary and secondary levels.

In the last five years, government spending on education has risen sharply — to $83 billion last year, up from less than half that level before. Schools now offer free lunches, which has helped raise enrollments to more than 90 percent of children.

But most Indian schools still perform poorly. Barely half of fifth-grade students can read simple texts in their language of study, according to a survey of 13,000 rural schools by Pratham, a nonprofit education group. And only about one-third of fifth graders can perform simple division problems in arithmetic. Most students drop out before they reach the 10th grade.

Those statistics stand in stark contrast to China, where a government focus on education has achieved a literacy rate of 94 percent of the population, compared with 64 percent in India.

Mr. Premji said he hoped his foundation would eventually make a difference for tens of millions of children by focusing on critical educational areas like exams, curriculum and teacher training. He said he wanted to reach many more children than he could by opening private schools — the approach taken by many other wealthy Indians.

Mr. Premji, whose total wealth Forbes magazine has put at $18 billion, recently gave the Azim Premji foundation $2 billion worth of shares in his company. And he said that he expected to give more in the future.

Those newly donated shares are being used to start an education-focused university in Bangalore and to expand and spread programs like the one here in Uttarakhand and a handful of other places to reach 50 of India’s 626 school districts.

The effort’s size and scope is unprecedented for a private initiative in India, philanthropy experts say. Even though India’s recent rapid growth has helped dozens of tycoons acquire billions of dollars in wealth, few have pledged such a large sum to a social cause.

“This has never been attempted before, either by a foundation or a for-profit group,” said Jayant Sinha, who heads the Indian office of Omidyar Network, the philanthropic investment firm set up by the eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Although the results in Uttarakhand are promising, they also suggest that progress will be slow. Average test scores in one of the two districts where the foundation operates climbed to 54 percent in 2008, up from 37.4 percent two years earlier. (A passing mark is 33 percent or higher.) Still, only 20 of the 1,500 schools that the Azim Premji foundation works with in Uttarakhand have managed to reach a basic standard of learning as determined by competence tests, enrollment and attendance. Nagla is not one of the 20.

“We are working with the kids who were neglected before,” said D. N. Bhatt, a district education coordinator for the Uttarakhand state government. “You won’t see the impact right away.”

The Azim Premji Foundation helps schools in states where the government has invited its participation — a choice that some educational experts criticize because it seems to ignore fast-growing private schools that teach about a quarter of the country’s students, including many of India’s poor.

Narayana Murthy, a friend of Mr. Premji and chairman of Infosys, a company that competes with Wipro, said he admired the Premji Foundation’s work but worried it would be undermined by the way India administers its schools.

“While I salute Azim for what he is doing,” Mr. Murthy said, “in order to reap the dividends of that munificence and good work, we have to improve our governance.”

Mr. Premji says his foundation would be willing to work with private schools. But he argues that government schools need help more because they are often the last or only resort for India’s poorest and least educated families.

Mr. Premji, whose bright white hair distinguishes him in a crowd, comes from a relatively privileged background. He studied at a Jesuit school, St. Mary’s, in Mumbai and earned an electrical engineering degree at Stanford.

At 21, when his father died, Mr. Premji took over his family’s cooking oil business, then known as Western Indian Vegetable Product. He steered the company into information technology and Wipro — whose services include writing software and managing computer systems — now employs more than 100,000 people. He remains Wipro’s largest shareholder.

While the foundation has been welcomed by government officials in many places, the schools in Uttarakhand provide a glimpse of the challenges it faces.

After visitors left a classroom at Nagla school, an instructor began leading more than 50 fifth-grade students in a purely rote English lesson, instructing the students to repeat simple phrases: Good morning. Good afternoon. Good evening. Good night. The children loudly chanted them back in unison.

Another teacher later explained that the instructor was one of two “community teachers” — local women hired by a shopkeeper to help the understaffed school. Although under government rules Nagla should have nine trained teachers for its 340 students, it has only four.

Underfunding is pervasive in the district. But so are glimmers of the educational benefits that might come through efforts like the Premji Foundation’s.

Surjeet Chakrovarty, now a 15-year-old secondary school student, is a graduate of Nagla and still visits his old school regularly. The son of a widower who is a sweeper at a local university, Surjeet aspires to become a poet and songwriter — something he attributes to the encouragement of his former teachers at Nagla.

“My teachers here gave me so much motivation to write,” he said.

One of those Nagla teachers, Pradeep Pandey, shared credit with the Premji Foundation, and its assistance in developing new written and oral tests.

“Before, we had a clear idea of the answers and the child had to repeat exactly what we had in mind,” Mr. Pandey said. “We can’t keep doing what we did in the past, and pass them without letting them learn anything.”

Source: NYTimes